Emergency Survival

In the Desert Southwestern US

Heartache, Heartburn

And

Sunburn

The Basics

Copyright©2006 NineLives Press

All rights reserved

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS 3

INTRODUCTION 8

SECTION 1: CLOTHING 14

SECTION 2: WATER 25

SECTION 3: THE BODY POLITIC 33

SECTION 4: NAVIGATION TOOLS 40

SECTION 5: LOST? 62

SECTION 6: STRANDED? 65

SECTION 7: USING THE EYES AND BRAIN 69

SECTION 8: MECHANICAL DIFFICULTIES: 76

SECTION 9: COMMUNICATIONS 79

SECTION 10: SURVIVAL AND EMERGENCY SUPPLIES 90

SECTION 11: THE METAPHYSICS OF SURVIVAL 103

SECTION 12: WILDLIFE 109

SECTION 13: OTHER DESERT FAUNA 114

SECTION 14: CRASH KITS 121

SECTION 15: CONCLUSION 125

TABLE OF FIGURES AND ILLUSTRATIONS 128

INDEX 131

INTRODUCTION

The potential range of human experience includes finding ourselves in unanticipated dangerous situations. Most of those situations have been examined minutely and described in print in the form of survival manuals. Desert survival is not an exception. Excellent books are available to explain primitive survival in the desert southwest duplicating lifestyles of Native Americans a thousand years ago. That is not the intent of this book.

A few decades ago I had an acquaintance with a man named Walter Yates. Walter had the distinction of surviving a helicopter crash in the far north woods by jumping into a snowdrift before the impact. He managed to survive winter months with almost nothing except the clothes on his back when he jumped.

Walter’s experience was a worthy test of human potential for emergency survival in extreme conditions. The margin for error was microscopic. The reason he survived rested on his ability to quickly detach his mind from how things had been in the past, how he wished they were, and accept completely the situation he was in. He wouldn’t have made it out of those woods if he couldn’t rapidly assess his new needs and examine every possibility of fulfilling them. “It’s all in the mind,” he once told me.

The margin for error in the desert is also narrow. That margin is dehydration. Extremes of temperature are also a factor, but they are more easily managed than the needs of the human body for water. Anyone who survives an unanticipated week in desert country did so by either having water, by carrying it in, or finding it.

Over the years I’ve followed a number of search and rescue accounts and discussed the issue with searchers. The general thinking among those workers is that a person missing in the desert southwest should be found or walk out within three to five days. After three days the chances for live return spiral downward. Returns after five days are lottery winners. When a missing person isn’t found within a week, it’s usually because he’s been dead for five days.

This book is to assist in avoiding situations that lead to the need to survive those crucial three days, and to provide the basics of how to walk out and how to find water in the desert southwest. If you need the emergency information here it will be because you became lost, stranded by mechanical failure, or physically incapacitated. I won’t address the bugs and plants you might find to eat. If you have water you’ll survive without eating until rescue.

When this book was written I had a close association with New Mexico State Search and Rescue (SAR). I was also writing a book about a lost gold mine at the time. The State Search and Rescue Coordinator (SARC) knew about the book. I had a special arrangement with him because I was spending a lot of time in remote canyons searching. If something delayed me there I didn’t want them to send out the SAR guys to look for me.

One day in the coffee room SARC asked me about my progress in the search and the gold mine book. I explained the lost gold mine search to him and how the information available in the past was sketchy.

“So you’re writing a book that’s likely to cause flatlanders to go out into the desert searching for this thing?”

I thought about it a moment before I answered. “It might. A lot of people would have tried anyway, but this book might bring in some who wouldn’t have come otherwise.”

SARC glared at me. His whole world revolved around flatlanders getting lost in the mountains or desert. Several times every month they’d scramble the forces to try to locate someone misplaced. Sometimes it’s a brain surgeon from Houston who got himself mislocated mountain climbing on the east face of Sandia Mountain within sight of Albuquerque . Other times a physicist from California gets off the pavement in the desert and loses his bearings. Sometimes SAR arrived in time to save their lives. New Mexico back country can be unforgiving.

“If you’re going to publish a book that will take a lot of idiots out where they can get into trouble you’d damned well better include some warnings on desert survival and how they can stay out of trouble! I don’t want to spend the next five years dragging the bodies of your readers out of the arroyos in body bags.”

That conversation ultimately resulted in this tome.

The New Mexico Search and Rescue (SAR) Coordinator (SARD) sneers because people in trouble in the wilds nowadays think they can call SAR with their cell phones, but only after they discharge the batteries on the GPS (Global Positioning System) so they can’t give coordinates of their location.

What he says is only partly true. People who can’t program a VCR probably won’t learn to use a GPS, either. And cell phones have a nasty habit of flashing “NO SERVICE” in little red letters when you try to use them in remote areas.

I’m including a few basic elements of back country survival for Texas , New Mexico and Arizona which might or might not be influenced by technology. Those who haven’t experienced the painful bite of desert beauty might find these suggestions helpful.

Figure 1 – Practical desert headgear

A great choice in headgear for the desert. The straw is cool, absorptive and breathes. The brim protects everything below from direct sunlight burning and glare.

Figure 2 – Abandoning aesthetics

A cap with the longest visor you can find is next best.

SECTION 1: CLOTHING

Ideally when you find yourself in a survival situation you’ll have arrived in that condition as part of a camping, hunting, fishing, or backpacking venture. In that case you’ll benefit from having intentionally planned your clothing for the back country. Hopefully the information below will assist you in that planning. However, the alternative possibility is that you came to be there with no intention for doing so, dressed in street clothing. You might be there as a result of a forced landing of a small plane, or of an impulse decision to take the scenic tour off the main highway for a break.

Throughout this work I’ve tried to allow for both contingencies.

HEADGEAR:

Wear one. The reason for the sombrero is the desert sun. Necessity was the real mother of the invention, despite the spiffy looks.

A gimme cap will do if you turn the bill forward to shade your nose from sunburn and your eyes from glare. Wear a handkerchief under the back to protect your neck and give you a spicy Beau Geste look. Save the backward and sideway bills for back in town when you are planning your next drive-by.

The superior headgear for the desert has the longest visor.

If you’ve seen pictures of German Afrika Korps Field Marshall Rommel, the Desert Fox of WW II you might have asked yourself why such a handsome hombre wore a hokey headgear. My guess is that Rommel preferred his nose without a sunburn.

If you find you don’t have a hat you’ll need to improvise one. A tee-shirt or bandana might serve, or a bonnet improvised from seat-covers. A bill-type sunshade to protect your face and the tip of your nose might be fabricated from the sun visor from your car. Whatever you choose, protect your nose, the tips of your ears and the back of your neck from direct sunlight exposure. Ignore aesthetics.

LONG TROUSERS:

A must. Protect your legs from the sun, and from whatever else bites, scratches, stings, sticks, or festers. This includes almost everything in the desert. Tough cotton materials are best, breathe better and are a lot cooler than synthetic fabrics. They’re also not prone to snagging on every thorn or bush you rub against. Khaki trousers with button-down cargo pockets are great unless the front pockets are sewed top-to-bottom to the forward part of the pants-leg. Front pockets that go horizontal every time you sit or recline dump everything in the pocket out on the ground. But pockets in the desert, pockets on shirts, vests, trousers, jackets, pockets for knife, jerky, compass, mirror, fire starter, maps, pockets are something you’ll come to love.

If you arrived unexpectedly and don’t have long trousers, improvise. Construct a long kilt or bib from a blanket, seat covers, anything to give protection from the sun and terrain.

LONG SLEEVES:

They help too. You can roll them up if you like, but rolled down they protect your arms the way long pants protect your legs. Cotton’s best, coolest and most durable.

FOOTWEAR:

Footwear improvisations. In the awful event you find yourself without any protection for your feet it will be necessary for you to improvise. The ancients trod this land wearing nothing but yucca sandals. You have more options. The floor mats on your car are a possibility and will survive longer as a pair of improvised moccasins than a lot of the dress sandals and high heeled shoes. Those high heels can be lopped off leaving the rest of the shoe as a base. Floor mat soles duct taped in place will give a few miles of wear. If you’re caught without appropriate footwear you need to think outside the box and be prepared to use any resource to remedy the situation. You absolutely need foot protection. A pair of bath thongs might provide the soles, seat covers, the tops, held together by duct tape. The thick nylon canvas from a collapsible camp chair might serve. The thick, carpeted mat over your spare tire in the trunk is worth examining. But whatever you finally use, before you leave the resource and security of your vehicle the protection of your feet is a concern you can’t ignore.

Street shoes. If you’re caught totally unprepared and find yourself with only a pair of wingtips to carry you in rough country for a few days you’ll be well advised to have a roll of duct tape handy to carry with you on your trek. Before you leave the vehicle cut several sole-sized pieces out of the floor mats for later use when the desert takes a toll and you’ll be glad for any footwear. Those improvised soles duct-taped to the bottoms of your shoes and wrapped across the top will provide an insulation barrier between your flesh and the burning ground.

Sandals are great, cool, and otherwise nice in the right environment. Walking in the desert isn’t one of them. They sunburn the tops of your feet and allow stickers and thorns easy access to the sides. Your feet will cook top side, blister bottom side, and bleed in between.

Cowboy boots and Wellingtons ride too generously on your feet. You’ll blister, slip around on rocks, and your feet will have lots of room to explore without going anywhere. They give no ankle support and general poor footing. If the soles are leather you’ll lose your footing on every smooth rock or slick surface. A hot, bad choice.

Sneakers, at least, with socks, are going to be your blessing if you get into trouble and have to walk a long way. When your shoes give out, you’ll be finished walking. Good hiking boots with waffled soles and ankle support are better.

Stockings. For long treks the pair of thick cotton athletic socks between your flesh and the surface of your shoe is a great invention. If your feet are the piece of your anatomy you are depending on to carry you where water comes out of a faucet you’ll want to take care of them. A good pair of socks is a long step in the right direction. A second, clean pair in your pocket is another good step. Once they’re moist with perspiration you can rotate them, placing the extra pair inside your shirt to dry while the other pair holds down the fort.

UNDERSHIRTS:

The tee-shirt was invented before the Hard-Rock Café. The Rolling Stones World Tour, the New York 10K Fun Run and Taos Ski Basin weren’t the reason our grandfathers wore tee-shirts next to their skin in those primordial days before the invention of air-conditioning. A tee-shirt underneath your shirt will keep you cooler days and warmer nights. It’s as simple as that. It can also be used to filter bugs out of pond water, bandage, or as a flag to attract attention.

DRAWERS, UNDER SHORTS, UNDERPANTS AND PANTIES.

Jockey or boxer? It’s an important consideration. Here’s the reason:

There used to be a phenomenon affectionately known among soldiers as ‘crotch-rot’. It was a fungal eruption of the groin resulting from wearing drawers moist from perspiration while walking. The material is abrasive when wet, rubs away the epidermis softened by the moisture. Once the skin is broken the floral Gestapo kicks down the door, tears up the furniture and sets up housekeeping. Boxer shorts are somewhat less prone to cause chafing than the more confining, sexier jockey shorts.

But whatever you’re wearing, when you sense the material moistening along the seams and rubbing your groin it’s time to go primitive. The relaxed, free swinging attitude of the person not wearing underwear is a major plus among those lost in the desert. A person in trouble doesn’t need the kind of pain that accompanies crotch-rot as a distraction.

Shed those shorts and use them for a handkerchief or head-cover at the earliest hint of chafing. Nylon underpants and panties are evidently in use by both sexes these days. I’d guess there’s no moisture absorption in the material and they’re probably hot, though I’m only guessing. Pantyhose definitely have no business on the human body in the desert. Once removed they might have many uses, such as providing an initial filter for desert pond water.

VESTS, JACKETS AND COATS.

Desert nights are frequently cold despite the daytime heat. If you’re traveling in the desert it’s worth keeping a jacket or windbreaker in the vehicle. If you get stranded you’ll be glad.

Windbreaker jackets: One of my favorites is a hooded nylon shell jacket that folds into the pocket and zips shut to make a small bundle to fit anywhere for carrying. This allows it to be there whenever the need arises, and while it’s light and small in the compressed state it provides considerable shelter from the wind and cold. Hooded sweatshirt jackets are also a good alternative.

Vests: If you’re lucky enough to be the kind of person who believes vests to be an essential part of the well-dressed man you’ll probably have one. Otherwise you’ll never know the joy of having a hundred pockets available. When a vest is loaded with everything you need to trek for a few days you can dump it off on the ground quickly, stretch, breathe, and be ready to move again in a moment. I’ve worn out many of these through the years and several more are hanging around the house waiting for my next day-trip.

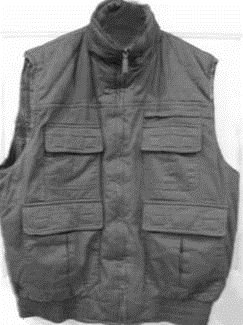

Figure 3 – Pockets for the well-dressed distressed

I’m evangelical about vests as a means of appearing to be a real cool old guy while in town. But it’s a puzzle the aboriginals among our ancestors survived long enough without all those pockets to come to town and invent television sets.

SUSPENDERS, GALLUSES AND BELTS

There’s a remote possibility you’re one of those stodgy, fuddy-duddyish people who don’t go about wearing suspenders. Maybe you don’t even own a pair. In that event you’ll need to improvise if you get yourself into car-trouble and have to walk out of a remote area.

Your trousers pockets will be filled to capacity with knife, compass, and all manner of useful objects you need. They’re too heavy to allow the simple friction lock between the trousers surface and your skin to keep your pants up. The result is that you’ll constantly tugging at your belt-loops, or finding your pants around your ankles.

Fabricating a pair of suspenders is easy once you recognize the need. A belt or camera strap threaded through a belt-loop in back, strung across your shoulder and tied into a front belt-loop will do in a pinch. Similarly, a couple of lengths of rope or cord crossed in back and tied in front will do the job. But if your jalopy is a total-loss the best answer to the problem will be to cut a seatbelt out and use it to improvise a pair of galluses you can be proud to wear. The width of the straps will ease the wear and tear on your shoulders. If your trek lasts a few days this can be a significant influence on your physical misery threshold.

SUN BLINDNESS AND EYE PROTECTION

If you don’t have any dark glasses you need to anticipate the possibility of impaired vision by sun blindness, even if you’ve been conscientious about wearing a hat with a brim, or bill. A few days in the sun mightn’t cause your vision to blur, but it sometimes does. Prepare for the possibility early, while you have resources. A mask made from fabric or plastic with narrow slits to allow you to see while keeping out the glare is quick and easy. It won’t take much room in your pocket, but it might become a possession you value.

SECTION 2: WATER

H20 you bring with you:

Carry 10-15 gallons of extra water in the vehicle, only for use in emergencies. Carry more water than you think you could possibly need in the daypack every time you plan to get out of sight of the vehicle or camp.

Water you find in cow-tanks, streambeds, pools, tinajas, cienagas, etc:

Figure 4 – Portable Water Filter

It’s worthwhile to carry a First Need or other similar water filter with filtration down to a couple of microns for protozoa. Halizone or iodine tablets are also useful for virus removal. Boiling works as a last resort, though it won’t remove the bug larvae carcasses. Water you find in the desert is usually considered the property of a variety of other creatures, most of whom have already filed a claim.

Water Filters and Purifiers:

Desert water tends to have a lot of tasty nitrogen from critter urine along with heavy microorganism counts. It also usually carries a massive organic loading from the swarms of visible animalcules taking swimming lessons. Filters will help remove a lot of this. If your inclinations don’t include providing pathogens with a house and 40 acres in your lower gut, a filter is a good alternative. Introducing new flora and fauna to your viscera works about as well as bringing a new feline into a house full of tomcats.

If you haven’t experienced Giardia, ask someone who has. They’ll have vivid memories they want to share.

A wide price and utility range of portable water-filters and purifiers is available from camping and outdoor suppliers. These vary widely, also, in effectiveness. Some depend on clear water to allow ultra-violet light to destroy micro-organisms. Others use filtration, a combination of filtration and chemicals and UV, or simply chemicals. These devices also range in size from that of a marking pen, upward.

In the event of a survival situation, any water purification device depending upon replaceable batteries, or clear water, mightn’t be the best choice. Although any purification is better than none, a single organism can proliferate a full-fledged Giardia event.

The compromise in size, weight, price and convenience, as opposed to utility is an important, individual choice. The process of selecting a camping, travel, or survival water purification device is important enough to justify examining the technology, the marketplace, and the personal plans of whomever the device is intended to serve.

Pre-filtering: Most of the organic loading and particulates found in pond water and elsewhere in the desert are too large to pass through a 3 micron filter. For this reason the filters clog quickly, slowing, then stopping passage of water through the filter medium. Some filters allow backwashing to clear out such debris, but without clean water to use as a backflush this provides little help to extend the life of the filter.

Adding a pre-filtering stage helps get the insect larvae, sand particles and algae out before the real filtration for micro-organisms begins. If the turbidity of the water is high, sometimes more than one pre-filter if advisable.

A nylon stocking or panty-hose, for instance, can be placed ahead of a tee-shirt or handkerchief on the inlet of the smaller filter. This will reduce the workload of the 3 micron filter, allowing it to only catch particles smaller than those passing through woven cotton material.

Figure 5 – Getting water from the soil

Solar Still

If you are stationary in the desert one thing can extend your survival long enough to have you eating grasshoppers and lizards. Water. In the southwestern US desert the number of options available for getting water is limited. Most of the cactus listed as sources in survival manuals of the past the past are rare and protected by Federal Environmental Statutes. If you can’t find a windmill you are limited to using methods of drawing water molecules trapped between the soil particles and capturing it for your own use.

The desert solar still is the best method I’ve ever seen for accomplishing this end. The still will produce approximately a quart of pure water per day in baked hardpan soil. In a moist, sandy arroyo bottom it will produce much more. Four such stills will yield enough water to keep a human alive long enough to die of starvation.

1) Excavate a hole in a channel bottom if you can find one. The top opening diameter of the hole needs to be small enough to allow complete coverage by your plastic sheet. The inside surface area of the hole has a direct bearing on how much water is produced. Larger surface areas produce more water. Damp soil gives more water.

2) Place a 1 quart or larger container in the bottom-center of the hole.

3) Secure the plastic sheet over the top of the hole with a few inches overlap on the sides. Leave enough slack in the sheet to allow it to droop 2-3 inches. Pile a berm of soil or sand over the overlap areas to seal the air inside the hole.

4) Place a small rock on the plastic sheet directly over the opening of the jar. This will create an incline on the bottom surface of the plastic with the lowest point being over the jar you’ll be catching water in.

5) Empty the jar once each day in the evening. Opening the hole more often will allow moist air to escape into the desert air.

Water from the soil will evaporate from the freshly excavated walls. The moisture content of the air inside the hole and the temperature difference between the outside atmosphere and the air inside the hole will cause moisture to condense on the bottom side of the plastic sheet. The weight of the rock on the sheet will cause condensation to flow to the lowest area, just over the opening to the jar and drip downward to be captured.

If you aren’t squeamish you’d be well advised to dig your latrines in the vicinity of the still. The body waste moisture you throw off will increase the moisture in the soil around the still, thereby providing more evaporation, more water.

If you don’t have a bottle or jar to catch the water a freezer bag or square of plastic will do the job. You just have to erect a frame to hold the top up and keep it open so the water can drip inside. A small circle of rocks at the bottom of the hole with a square of plastic laid over it overlapping the rocks will do. You’ll think of a way to get it out of the hole without spilling a single drop.

SECTION 3: THE BODY POLITIC

Heatstroke: Electrolyte depletion of the human body. Sunshine, heat, and liquid deprivation. Salt tablets probably don’t make much sense in normal life, but in the desert, they restore needed electrolytes to your body. These won’t be provided by most water you’d care to drink, no matter how loaded with microorganisms. Perspiration evaporates quickly in arid climates. Your body is throwing off a lot of salt, waste and other juice when it perspires so heavily. Salt tablets help restore some of it.

Hypothermia: Know what it is, prepare for it, watch for it, and avoid it. The desert gets cold at night. But a sweaty rest in a cool breeze can do it on a hot day. Simply stated, Hypothermia is loss of body heat. Evaporating body moisture from your lungs as you breathe, evaporation as you perspire, conduction of the body heat into the soil or rock surface where you’re resting, along with a cool, gentle breeze can bring it on unexpectedly. It can cause complete physical collapse.

The first requirement for hypothermia is noticing it in time to prevent it. The first sign is a malaise, a reluctance to move.

Paying close attention to the condition of your body, recognizing the symptoms and stopping it before it goes further is the way to deal with it.

1. Lie down.

2. Get warm.

3. Drink some hot water.

4. Beware of coffee, tea, or any alcohol.

Sunburn: Cultivating a nice tan while in town might be a fine idea. In the desert, in an emergency situation, protecting the surface of your skin from the sun is an absolute necessity. If you’re lost you mightn’t have the margin of error to risk a sunburn.

Insect bites and stings: Insects are the most dominate animal-life form in arid climates. They’re attracted to any source of moisture. Wherever you pause you’ll find biting flies, gnats, mosquitoes won’t be long in finding you. You’ll probably be blessed with a lot of irritating stings and bites.

A few years ago while backpacking I paused to rest against a huge, dead tree. I leaned against it with enough force to give it a slight jar. A moment later the air around me was filled with angry bees. The hollow of the tree was the home of a large wild beehive.

Most of my life I’ve dealt with bees and wasps under the erroneous assumption they can’t sting if you hold your breath and stand perfectly still. Some adult told me that when I was a child and I adopted it by habit. Although bees and wasps can certainly sting under those circumstances, they probably won’t. The fact I’ve never been stung by a bee and was not when I provoked them on that occasion attests to the fact it’s a worthy method.

After you’re bitten one means of drawing the swelling out of insect bites and stings involves packing mud over them in a poultice. If you’re not near a source of water you can make your own using urine mixed with soil. Aspirin, or pulverized cottonwood bark can also be used to reduce the itching and irritation. Similarly, a mud poultice made from the ashes of your fire might help.

Blisters, thorn punctures, cuts and abrasions: These are a fact of life in the desert. Basic treatment for punctures and blisters can be found in any first-aid text and are too much a part of common knowledge to justify repeating them here. However, the poultices described above might help. But for larger cuts a tube of super glue is worth making certain you keep with you in your pocket survival kit. A few drops will seal shut a wound that would have otherwise required sutures.

Severe pain: A thousand possibilities exist for the human body to experience pain in survival situations. Depending on the background of the person trying to survive, the consciousness and level of severity will vary with an identical injury.

In view of the fact the range of choices for reducing the pain is limited in such an environment a few observations and suggestions for homespun pain reduction techniques are probably appropriate, as well as an anecdote or two to illustrate that human beings carry with them the capacity to endure such trivialities.

Anger: One example of the power of anger for enduring pain and hard times can be found in the story of Hugh Glass. During the early 1800s he was attacked and mauled by a grizzly bear somewhere in the North Country . Two other well-known mountain men were with him, but they took his rifle, knife and provisions and left him for dead, convinced he’d die shortly.

Without food or equipment, Hugh Glass recovered enough to crawl and stumble several hundred miles to the nearest help, where he arrived with a promise to hunt down and kill the two men who’d left him there.

Similarly, another mountain-man, John Colter, was captured by the Blackfeet during roughly the same time period. His partner was slaughtered, but the aboriginals chose a different game with Colter. He was stripped naked and allowed a brief head start with the intended outcome being that they’d chase him down and the person who got him would have the satisfaction of hanging his scalp from the lodge pole.

During the chase Colter managed to take the spear away from his nearest pursuer and kill the man with it. Afterward, stark naked and equipped only with the spear and a blanket he’d taken from the Blackfoot, he trekked 200 miles through hostile terrain.

Anger is a strong anesthetic. If you’re overwhelmed with pain and don’t believe you can go another step, allow yourself the luxury of a dose of anger over how you came to be in this plight. Wife, sweetheart, mistress, your boss, and (especially) your outfitter are good targets for this anger.

Gratitude: The most profound, little-known and underutilized pain-reduction technique I’ve ever encountered is gratitude. It makes no sense at all, but it works. As a concept it’s a matter of allowing yourself to view every experience in life as a welcome growth experience, but in the instant of severe pain understanding the concept is secondary.

I first saw the method at work when my granddad was cranking a tractor and was knocked flat by kickback of the crank. “Thank you Lord!” Papa exclaimed, though he was a devout atheist. As he struggled to rise, bloody, face contorted, he said it again.

Afterward, when he was upright again and scowling at the offending crank I asked him about it. That’s when he explained to me that it “just damned well makes things quit hurting. I don’t know why.”

I’ve used that method for more than half a century and it’s only rarely failed me.

Give it a try if you don’t believe me. Find a hammer and place your thumb flat on the floor, nail facing upward. Draw the hammer back across your shoulder and smash the bejesus out of your thumbnail with all the force you can muster. Then, when the front of your head explodes with sunlight, say it. “Thank you Lord!” One way or another, you’ll be amazed.

Zen, Yoga and Reiki: If you’re interested in the various Asian spiritual healing and mind control techniques you’ll have to look elsewhere to find the details. However, I will say the use of mantras, for endurance and pain sustained pain relief, various Zen techniques, and Reiki have all contributed to my own life experience through countless injuries and ill-conceived adventures and treks. They can, and do help. But they’re mostly disciplines requiring time, practice and study. Once you’re submerged in an emergency it’s too late to attempt to adopt them.

SECTION 4: NAVIGATION TOOLS

Avoid becoming a lost soul.

Maps:

Digital Maps

Mapping technology is rapidly changing and while the basic information here is unlikely to become obsolete, mapping resources and availability are expanding at a shocking rate. Aerial photos and detailed images of almost every location taken from orbiting cameras. If you anticipate the area you’re going to get lost in I’d suggest you keep a printed copy of whatever such information you consider appropriate to your needs. Some facets of the technology as it applies to survival will be discussed at greater length later. However, Delorme Atlas and Gazetteer, described here is available on CD and allows a print function. Every reference to the characteristics of Delorme Atlas and Gazetteer here applies equally to the digital version.

Terms: You need to be familiar with three terms before discussing back country maps. Scale and Minutes refer to the way the map relates horizontally to the country you are in. Contour refers to the method the map uses to communicate vertical information about the terrain.

Scale:

1:24,000 is the scale for USGS Topographic Quad Maps. One inch on the map is equal to 24,000 inches, 2000 feet of terrain distance. Possessing 7.5 minute topo maps, and the ability to understand those helps a lot. They are published by the US Government and are a bargain, even at the prices charged for them today.

1:100,000 scale is used by BLM and several other US Government agencies One inch on the map equals 100,000 inches actual distance. 8333 feet per inch, or slightly over 1.5 miles to the inch.

1:250,000 is used for Delorme Atlas and Gazetteers and Roads of (Where You Are). Those show maps on a scale of one inch equals 4 miles. Both are good, showing a level of detail approaching the 30×60 Quads. These have the advantage of covering the entire state where you are.

Minutes

I’ve never understood the reasoning for doing so, but US Government agencies and other map gurus use the term ‘minutes’ to define the size of the area a map covers. The earth spins at a speed of 1000 miles per hour. It is 24,000 miles in circumference. Therefore, at the Equator, one mile passes directly under the sun every minute. A 7.5 Minute 1:24,000 scale USGS Quad covers an area 7.5 miles square. A 1:100,000 scale 30 x

Figure 6 – Contour Intervals and Topo Features

60 Minute BLM Quad covers an area 30 miles wide by 60 miles long.

Contour Intervals

The illustration at the beginning of this section shows a portion of a USGS 7.5 Minute Quad. A part of the emphasis of the map includes specific terrain features shown in contour lines. The wavy lines are parallel contour lines, each following a single elevation. On this example the contour interval is 200 feet because the ground surface is more vertical than horizontal. In flatter areas the maps use 40 foot contour intervals, or in near-level terrain, 10 foot intervals. Intervals also increase and decrease to correspond with the minute/scale of the map. A 30×60 Minute BLM Map for rough terrain has contour intervals of 20 meters. A Delorme Gazetteer has contour intervals of 200 feet for Arizona and 300 feet for New Mexico .

Figure 7 – Atlas features

Map from DeLorme’s New Mexico Atlas & Gazetteer ™

Copyright © DeLorme, Yarmouth , Maine reprinted by permission from Delorme, August 14, 2003 .

This illustrates the surprising detail on the Delorme maps for a remote area of New Mexico north of the Datil Mountains . The dotted lines are two-track dirt roads. The combination of shading, detail and contour lines render the map usable for motorized travel and trekking in spite of the fact the shaded squares are one mile square.

Note the watercourses depicted. Those are mostly just arroyos carrying water in immediate time of rainfall, although a person might occasionally find a pond or trickle in one if it’s not a dry year.

The shaded area on the lower side of the map depicts US Forestry Service land. The smaller shaded squares indicate the land is public within the squares. The color of the shading defines the public entity with ownership rights. Those on this particular map happen to be Bureau of Land Management and State of New Mexico . But on the same page of the Delorme Atlas Indian Reservation land is also depicted by a different color shading.

Also note the contour lines. By necessity a map of this scale loses a lot of detail because of the large area covered. The promontories on the right and lower-right qualify as mountains though the contour lines are few. Delorme has partially compensated for this by shading so map-users are aware of the terrain characteristics despite minimal contour lines.

The best map for your needs.

7.5 Minute Quads: Driving the back country in a 4×4 covers a lot of ground. If you are just exploring and don’t have a specific destination in mind you’ll have a lot of money and space invested in maps if you try to use USGS 7.5 minute Quadrangles for general navigating. They come flat and if you use them a lot you’ll want to avoid folding them, which wears them out. On the other hand, if you want specific, detailed information about the terrain you are trekking afoot or canyons you are exploring, the 7.5 Quad is the best you can get. I’d suggest buying 7.5 Quads for the area immediately surrounding your specific destination. There’s no excuse for ever getting lost if you have a 7.5 Quad folded up in your pocket. Almost no one who gets lost has one. If there are any dwellings, stock tanks, windmills, or major roads within 3 1/4 miles of the center of the quad you are on you’ll know where they are.

Folding BLM and USFS maps on a 1:100,000 scale are good for showing remote roads, but lack the detail of the 7.5 quads. They’re also more difficult to make sense of from the Long/Lat and UTM coordinates in the margins. However, some have the added advantage of identifying whether you are on private land, or public land. One set of the BLM maps even identifies whether the mineral rights are owned by the public, or are privately owned.

For general traveling off the pavement, a Delorme Gazetteer of the state you are in, or a THE ROADS OF (STATE YOU ARE IN) is a minimum. You need a printed document showing unpaved, minor roads. Folding state roadmaps of the interstate won’t help if things go sour. Knowing you are in Graham County, Arizona tells you something about the kind of sunset and amount of rain you can anticipate. Not much more than that. On the other hand, knowing the faint two-track heading off to the northeast will get you to a windmill five miles away might be a lifesaver.

The differences between THE ROADS OF (STATE YOU ARE IN) and Delorme Gazetteer are mainly in which details the mapping company chose to emphasize. The THE ROADS OF (STATE YOU ARE IN) tends to show cow trails that might be absent on the Delorme product, along with windmills, houses, cemeteries that might well be long-abandoned. However, contour lines and shading of land-use/ownership I’ve described on the Delorme product are not on Roads. My on preference is to carry both. There are battered and dog-eared copies of each of the two for several states stored in my vehicle. I frequently cross-reference between the two.

However, from a strictly survival perspective I’d suggest Delorme.

Figure 8 – Triangulation

Locating yourself by azimuths and triangulation

I’ve always been surprised how few backwoods trekkers know how to use a map and compass for locating themselves. I’ll discuss some aspects of the method below, but the basic concept is simple. It’s depicted on the illustration above.

From a position where you can view terrain features in the distance place the map on a flat surface. Note at least two distant landmarks within your view and indicated on the map. Take an azimuth on each of the two identifiable landmarks.

Now, place your compass on the surface of the map with the rose in the map position for due-North. Rotate the map until the compass needle is also pointing North on the compass rose.

In the illustration Cerro Brillante is 318 degrees from the position of the person taking the azimuth. Cerro Montosa is 250 degrees from the location.

Place your compass on Cerro Montosa and using a straight-edge, stretched string or tape with the edge beginning at the center of the compass create a line from the center of the compass along the reciprocal (250 degrees minus 180 = 70 degrees), the 70 degree line across the map.

Now repeat the process using Cerro Brillante as the center point from the compass and the reciprocal of 318 degrees (318 degrees minus 180 = 138 degrees), 70 degrees.

You now have your location at the point where the two lines intersect. You’ve taken azimuths on recognizable landmarks and triangulated those azimuths on the map.

Even if you find yourself with a map, but no compass, you can still locate yourself generally by knowing these techniques and using more primitive methods described below, such as the shadow stick, or your watch to find rotational east/west and extrapolating the compass rose on the ground.

This simple process of taking azimuths and triangulating your location on a map is one of the most fundamental concepts of navigation. By understanding the process, practicing it, and developing a habit of using it frequently whenever you’re in unfamiliar terrain you can spare yourself most incidents involving being lost. You can also ease the worries and efforts involved in getting yourself un-lost whenever you lose your bearings.

Men have been using triangulation as a means of navigating from earliest recorded history, yet the knowledge of how to do it resides in a relatively small fragment of the population. Mariners, pilots, surveyors and a few conscientious backpackers appear to be the last bastion of pre-technology skills for knowing where we are on the surface of this planet.

This bi-product of technology dependence manifests itself in many ways in a backwoods setting, beginning with the fact trekkers frequently don’t even notice landmarks they pass that could assist them in getting out of otherwise dangerous situations when technology fails.

The azimuth, the understanding of triangulation techniques, knowing that shadows are on the west sides of objects in the morning, the east sides during the afternoon are the foundations for a world view to allow you the freedom of knowing where you are without trying to remember which side of trees moss grows on (it doesn’t).

Casual observation along your route, making mental notes of your general direction of travel, allowing yourself to indulge your curiosity to consult a map about the name of that promontory you’ve been seeing off to the northwest will all increase your non-crisis enjoyment of whatever place you’re traveling in. If you do so as a matter of habit you’ll find when an emergency situation develops it will usually be the result of mechanical failure. Otherwise you might well suddenly discovering you’ve been daydreaming about the giant television you want, and the road just ended at an arroyo, and you don’t have a clue where you are.

But even then, if you know the basics of map and compass navigation you will probably live to see something on that giant television.

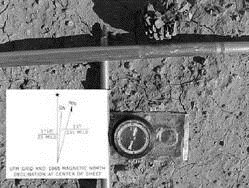

Compasses:

Carry two compasses, so you won’t be tempted to believe one of them is wrong. Know the compass declination for the area you are in. The compass on the hilt of your survival knife isn’t something you want to depend on. Buy a high quality compass and back it up with a cheaper one from the discount house. As a minimum it should have a rose on it showing 360 degrees on the face. The instrument will serve you better if the rose turns on the face so you can calculate magnetic declination.

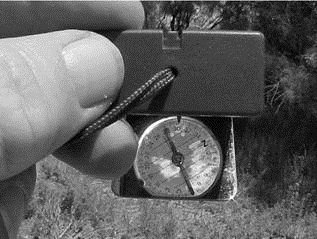

This is my personal favorite among the compasses I’ve used. It’s called the Swiss Army Compass and I imagine it bears as much relationship to the Swiss Army as the Swiss Army knife has to that worthy body of men.

Figure 9 – Lensatic Compass

But the Victorinox Swiss Army compass combines economic pricing and quality in ways the Swiss Army knives no longer do. The instrument is ‘lensatic’, meaning it’s designed to allow viewing the rose while sighting on a terrain feature in the distance. This allows for more precise readings than can easily be obtained from a flat compass. The term for this process is called ‘shooting an azimuth’, or ‘taking an azimuth.’ The illustration over the heading, Compasses, shows two azimuths intersecting to triangulate on the position of the person shooting the azimuths. Before the advent of the GPS this was the most reliable method for getting a ‘fix’ on your exact location. It’s still a good technique if you don’t have a GPS or you’ve allowed the batteries to die.

The compass in the photo slides into the plastic case in the upper half when not in use. It comes with a lanyard for easy accessibility and transport. The groove running vertically through the picture is a sighting groove. The three white lines in the groove are luminous to allow for use in low lighting conditions. The rose rotates on the surface to allow precise azimuths while holding the compass at eye-level while sighting. When closed the box is approximately two inches long by 1.5 inches wide and 3/8 inch thick. It’s durable and dependable. I’ve carried the one in the illustration for twenty years. Even though it’s seen hard use that compass is as good in 2003 as it was in 1983.

The discount houses are full of lensatic compasses built on the US Military model. They are cheap, and usually they don’t work well. If you are determined to make do with a cheap compass you’ll be far better off buying one designed for flat use.

If you want a lensatic compass you can choose one similar to the one in the photograph, or you can visit a surveyor supply store and get a good, durable lensatic instrument. My general opinion is that you are best off staying away from military models other than the Victorinox.

Figure 10 – Compass Rose and Mirror

When you open the case on the Victorinox a mirrored-steel plate drops down to allow you to view the rose and take a reading while sighting through the groove along the top of the compass.

Figure 11 – Sighting a lensatic compass

I mentioned earlier that I believe you should carry two compasses into the wilds. I consider the one shown to be a good choice. It’s a Silva, tough, cheap, and dependable. I’ve carried that one more than a decade. As you can see it’s battered and scarred, but it still works. I usually keep it in my pocket emergency kit along with other items I don’t want to be caught without.

Figure 12 – Flat compass with rose

This particular design for a compass is intended to be used flat on the surface of a map. The straight edges and the scales along the sides are useful for alignment by placing the edge along a section line or lat/long line to get a heading direction. In this sense the flat model instrument is actually better than the lensatic.

Figure 13 – Wrist watch for a compass

Using a wristwatch for a compass:

The watch in the picture is a Timex Expedition made especially for use as a compass. The bezel is a moveable ring compass rose. In the morning sunlight point the arrow on the lower right side of the bezel at the sun and the arrow on the top of the bezel will point rotational north. In the afternoon sunlight the arrow tab on the lower left performs the task.

Any watch or clock will serve the same purpose. Point the space between 3 and 4 at the sun in the morning and 12 is north. Point the space between 8 and 9 at the sun in the afternoon and 12 is north.

GPS dependence:

If you are depending on the GPS to get you back to the car, to camp, or to safety, don’t keep it turned on all the time. Depleting the batteries will ruin your day if you haven’t taken the time to learn ground reference navigation with a compass and map. Let the magic instrument give you a magnetic compass heading to your destination, then give the batteries a break. Turn it off and put it away. Use the compass to shoot an azimuth on a distant landmark in the approximate direction you are going, and put that away, too. Pay attention to the country around you and not to the ground immediately in front of your feet, the compass rose or the whispers and complaints from the display on the GPS.

Know how to translate the coordinates displayed on the GPS to a position on the map. The numbers displayed on the GPS screen represent one of two types of coordinates: These are Long/Lat, and UTM (Universal Transverse Mercator). The UTM coordinates are easiest to use. If you prefer one coordinate system over the other, you can go into the setup menu on the GPS, under COORDINATE SYSTEM, and instruct it to give you coordinates of that type.

When you find yourself in trouble take a fix of where you are. Write down the coordinates. If your vehicle is stranded it might save you a lot of trouble and money relocating it. Keep a mental record of what direction you are moving away from your vehicle and try to form a rough idea of how far you’ve gone. If you eventually get cell phone contact and you can give them your coordinates the rest will flow smoothly.

Detailed maps for remote areas usually carry both sets of coordinates in the margins to allow you determine your position or destination on the map in terms of those coordinates, and then feed the coordinates to the GPS. That’s useful information. You can double-check where you think you are against the exact position determined by the GPS. You can also feed in the coordinates for your destination to allow the GPS to tell you how far you have to travel. And when you leave your vehicle on a nondescript mountain road you can rob yourself a lot of healthy walking by taking a fix with the GPS and saving it under the heading, ‘TRUCK’.

However, carry a set of spare batteries and rotate them frequently.

GPS technology is changing rapidly, adding all manner of electric maps and gadgetry for you to play with. But nothing I say here should become obsolete, no matter what space-age piece of breakable plastic powered by batteries with a limited life-span you have in your pocket.

SECTION 5: LOST?

When you begin to wonder if you might be lost, you are lost. That’s the rule of thumb. Believe in it from the first nagging wiggle at the corner of your mind.

Whether you are on foot, or in a vehicle, that is the moment to stop, relax a few minutes and consider your situation. Any further travel without knowing where you are is possibly going to make things worse.

The first sign of trouble

A lady I once knew, an experienced backpacker, left her toddler son and hubby to step behind a bush to pee. She didn’t carry anything with her. She hasn’t been seen since. They never found her body. Disorientation comes easy in rough country, even to seasoned woodsmen and desert rats.

When you get into trouble in any remote area but maybe aren’t ‘lost’ yet, the first inclination is to go into a fit of cursing or remorse. The rock that has your differential high-centered, the rubber pom-pom that used to be a fan belt, steam escaping from a radiator hose and the pool of oil accumulating under the bash plate are all Fate’s way of telling you to slow down. The pressures of modern life have conditioned us to see such blessings in a negative context. After the cursing or self-pity, a lot of people move on to frantic, counter-productive activity.

When one of these events happens in a remote desert area quiet reflection, moderation, and a carefully considered plan of action stands the best chance of making your day go better. Anger might be okay when there’s a margin for error. During those first moments after you discover you are stranded or lost you don’t know yet whether you have the luxury for anger. Respect the potentials.

Stop and think. Breathe slowly and reflect on your situation. Think smart. Don’t move before you pause, consider everything and have a plan of action.

This might involve taking a long look at the maps you wisely carried along with you. Try to establish your exact geographic location. Inventory the water and equipment available to you. Consider how you will protect yourself from the sun, and cold. Look at all the possibilities.

Do your inventory with imagination and look for anything you might find useful. That plastic grocery bag was trash a little while ago. Now it might be treasure. The mirror on the back side of your windshield visor might belong in your pocket. If you are going to have to walk, consider your clothing, your shoes, how much water to carry, and where, exactly, you think you are headed.

SECTION 6: STRANDED?

Walk, or remain with the vehicle or grounded aircraft?

The conventional wisdom in situations involving a forced landing in an aircraft or mechanical failure of a vehicle is that you should remain near it. Search and Rescue workers will present that as the 11th Commandment.

The reason for this rides on the assumption that the aircraft or automobile will be easier to see from the air. Anytime rescue workers find the mode of transportation without also finding the person they’re searching for their lives become a lot more complicated.

However, rules of thumb are always dependent upon a number of possibly erroneous factors. The airplane, they assume, was flying on course between two known destinations, for instance. The craft is located in a position to allow it to be seen, as opposed to being hidden from sight. If an automobile is involved, the rule of thumb assumes someone within the confines of civilization was expecting the stranded travelers to arrive somewhere and will set the search engines in motion.

If these conditions apply the best course is definitely to remain in place, turn on the Emergency Locating Transmitter (aircraft), or set the emergency flashers going on the vehicle after dark, and wait for help to arrive.

However, if the aircraft was in the air without a flight plan, circling around sight-seeing and was forced down in an area where it’s unlikely to be seen, followed by the discovery that the Emergency Locator Transmitter is missing or non-functional the decision to remain with the craft and hope for the best might be fatal.

Similarly, if the occupants of the stranded vehicle aren’t expected anywhere for the next two weeks, the scenario changes. If the people waiting somewhere are only able to give a location for search as ‘somewhere in West Texas , waiting at the vehicle might be a risky proposition.

The rule of thumb to stay with the plane or vehicle was created in the minds of experts based on statistical evidence that more people are rescued more quickly by remaining stationary. There mightn’t even be a statistic on how many died of thirst, exposure or injuries as a result of their belief in the 11th Commandment. Additionally, the rule of thumb supposes the person who decides to walk out is ‘average’. That is to say, the person has no idea where he is, how to improvise survival gear, how to find water, how to signal his location en route. The statistics would probably look a lot different if the average person wasn’t inclined to walk in circles.

It’s worth remembering that missing aircraft several years old are frequently discovered. A few years ago a business jet scattered across the mesa a few miles east of Santa Fe solved the lingering mystery of what had become of it. Despite a flight plan, a known starting point of Houston, and a known destination and arrival time for Santa Fe , years elapsed before the remains were located purely by accident. Any survivors of that crash would have been well advised to violate the 11th Search and Rescue Commandment.

Walking out:

After you’ve thoroughly, calmly and realistically analyzed your situation if you’ve made a decision to walk out the inventory and planning mentioned above gains importance. The vehicle or aircraft is a resource loaded to the gills with potential survival materials. Those potential resources need to be recognized and gathered prior to beginning your trek. The possibilities for survival items you might need later disguised as parts of the vehicle are described throughout this book.

If you are leaving people with the vehicle, make certain everyone understands the plan, and that the minimal needs of everyone are met. Everyone should know what is expected of them in the current circumstance, and in the event new developments arise sometime after you are out of sight of the vehicle. (Such as the arrival of a friendly rancher or someone noticing the wolf in the bushes is paying a lot of attention to Fido.)

If you leave your vehicle unattended, leave a note on it explaining what has happened, the direction you are headed, and what you intend. If there’s a phone number would-be rescuers can call to notify someone of your situation, leave that, too. This will help a lot in the unlikely event you don’t show up in a few days.

SECTION 7: USING THE EYES AND BRAIN

If you get into trouble in the desert, notice game trails, cow trails, and fresh droppings. Water might be somewhere at one end or the other of every trail. There’s a 50% chance your guess will be right. Where the game trails converge and increase in number, the chances for water increase.

It might sound strange, but even contrails can help. Notice over several hours or days what directions high altitude air traffic in your area marks itself. In a lot of remote areas a predominance of contrails are headed to the same airport a few hundred miles from where you are. If you notice a pattern of that sort and take a compass bearing on the apex of their destinations you can always know when you see a contrail that 082 degrees from you is probably right over that ridge to your right.

Lights. If you are on a high place in the desert you can see a long distance. Make sure you aren’t in a canyon at sunset. After nightfall look carefully in every direction for lights. Those lights are probably a dwelling. Shoot an azimuth.

If you find you’ve done the stupid (and we all have) and gone just a little way out of sight of all your gear, compass, GPS, everything, back at the car, or under a tree hmmmmmm I think back over there somewhere, you might be in trouble.

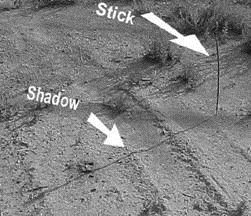

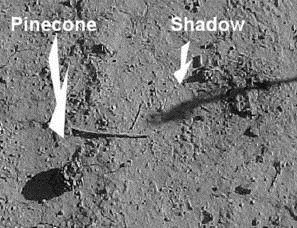

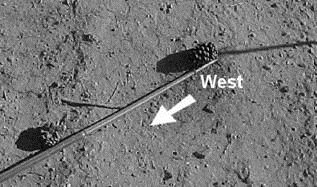

There’s a trick called a ‘shadow stick’ that might help if you’ve paid any attention to directions or can recall what was on the map you left with your gear. Put a 4’ stick into the ground, vertical.

Figure 14 – Shadow stick Step 1

Place a rock at the end of the shadow as shown in the next photograph. Then sit for a while and let your life flash before your eyes.

Figure 15 – Shadow stick Step 2

After 20 minutes or half an hour the shadow will have moved.

Figure 16 – Shadow stick Step 3

Figure 17 – Shadow stick Step 4

Place another rock, pinecone or other marker at the end of the new shadow location as shown below. You now have the basic instrument to give yourself a cool drink of water and a warm place to sleep tonight.

Figure 18 – Shadow stick Step 5

Draw a line between the two rocks. The line points east-west. The first rock you put down is always on the west end. You’ve established precise rotational east/west once you’ve placed those two rocks or pinecones and drawn the line between the two.

Figure 19 Shadow stick Step 6

Cross-hatch the line between the rocks, and you have a north-south-east-west rose before you. This is particularly helpful when the sun is high and the shadows so short you can’t really get a direction just by looking at them.

Figure 20 – Shadow stick completion

The end result

Without using a compass you’ve just established rotational East / West / North / South within a degree or three of being exact. At this point you should be feeling a lot better. If you came in on a road from the south and walked away from it on the left side of the road you don’t qualify as being ‘lost’ anymore. Even if your situation is more complicated you won’t be stumbling around in circles.

If you know the general direction you need to travel pick out a prominent landmark in that direction and use it for a goal so you don’t have to do this frequently. It’s also a good idea to look behind you and try to pick out another landmark there. That way when you wander off your course or can’t see the first landmark you’ll still have a reference point you know you should be walking away from. Similarly, if you note large landmarks to the left or right and keep them there as you trek your route will be more direct than it would be otherwise.

When you sit down to rest go through the same process again just to reassure yourself.

SECTION 8: MECHANICAL DIFFICULTIES:

Fan belts and hoses: Two of the peskiest problems in the backcountry. For some reason these two weak points in the mechanical system are responsible for the lion’s share of summer vehicle problems, along with stuck thermostats. Any one of the three can set you afoot by causing you to lose all your engine coolant.

An extra set of fan belts in the trunk, along with whatever tools are necessary to change one, is a smart idea. With the chicken noodle soup under the hoods of a lot of cars, this can be a problem, but it’s better than leaving a carload of equipment sitting out there while you go off to try to find your destiny in the desert.

Water hoses can be temporarily repaired by tightly wrapping the hose with electricians tape and refilling the radiator with the extra water you wisely brought along and wondered why. If the hose leak is too close to the clamp, an inch or two of hose can be usually be cut off, and the intact portion reattached under the clamp.

Tires: Make certain you have a good spare or two. Full sized. Street tires don’t hold up well on 2-track roads. The wheelbarrow tire provided as a spare by the auto dealership probably isn’t the best alternative for a 50 mile drive back to the pavement.

Jack: The thing provided in your trunk and represented as a jack is ok for changing a tire in the grader ditch of a paved road. For lifting your vehicle off a high center, a hydraulic jack is a minimum. A high lift handyman jack is better yet, if your bumper can take the strain.

4 Wheelers:

These vehicles are great for getting you one heluva long way off the beaten path. It’s easy to cruise along and not pay attention to exactly where you are. It’s also easy to assume you will be back in camp by suppertime. Keep in mind that 4 wheelers can have mechanical failures. Any vehicle capable of dumping you afoot more than a days walk from a drink of water needs some thought beforehand.

Fuel:

Bear in mind it’s a long way between gas stations, and that low-speed, low-gear driving burns a lot of gas. It’s a good idea to top off the tank every chance you get and go off the pavement in a car with a full belly.

SECTION 9: COMMUNICATIONS

Cellular phones. If you are broken down, injured, or lost in the desert a cellular phone might save you if you are careful. If the phone shows ‘No Service’ where you are, turn it off to save the batteries. Try using it again at night or from a hilltop where line-of-sight might assist you. Sometimes 50 feet of elevation will get you enough service to bring in the US Cavalry.

CB Radio. If you’re broken down in the back country and your vehicle has a functional battery you probably only need a CB radio unit to get help. People who live a long way from anywhere often use the CB to gossip with their neighbors in the evenings. No matter how far you get from civilization, if you turn on the CB at night you’ll hear people talking about cow-prices, rain prospects and Charlie’s pit-bull killing calves. The atmospheric density causes the signals to bounce at night. Evening conversations with people 50 miles away aren’t uncommon. If you are going into an area where a breakdown is possible I’d suggest buying a garage-sale CB/antenna combination for $5 to carry in your trunk, just for emergencies. Pick a hilltop and use the radio to tell your location and problem. While you’re waiting for rescue you can hear the funny stories about how Jim’s kid told the new teacher in town, “I don’t need to learn anything. I’m going to be a rancher.”

Fire: If you think they are searching for you, keep a fire going all night. Even if they aren’t searching, it might attract attention, especially if you are in an area where fires are forbidden. Think outside the box where fires are concerned when you’re in an emergency situation. If you hear a plane somewhere overhead at night, if the wind isn’t blowing, and if you’ve picked out an isolated tree while there was still daylight set it afire. The blaze will be visible from horizon to horizon. If you happen to be in an area where fires will bring a badge and gun to give you what-fer, all the better.

Smoke. Gather some cow or elk manure, or green wood and keep it near a small fire daytimes if you are stationary and on foot. The smoke or the smell of smoke might bring someone to investigate. This type of fire should be placed on a hilltop, or high up the side of a promontory to allow it to be seen from a great distance.

If you’re near a vehicle the crankcase oil, transfer case, and transmission lube saved to trickle onto the flames or coals will create a column of smoke worthy of the name. Similarly, the four tires removed from the ground, and the spare tire will each burn half a day with a resulting smoke column visible for miles in clear weather with low wind. The tires can easily be rolled uphill to the highest, clearest spot possible for this job. The odor of burning rubber can also be detected for long distances.

After the tires are gone the plastic dashboard, door panels, floor mats, foam seats, rubber engine hoses and fan belts will also provide a heavy smoke from a comparatively small fire.

If you don’t have a hose to siphon fuel out of the gas tank remember, at least, there’s a high octane signal nearby. As a last resort when you’re in a state of complete desperation thread a length of cloth through the fueling tube far enough to reach the gasoline. Wait for an airplane somewhere overhead, once the cloth becomes wet with fuel. Rig a torch or other means to allow you to be as far as possible away while you explode the fuel tank.

Mirror , shiny tin can lid, or CD. Almost anything to reflect sunlight. The methods for making and using a signal mirror are detailed below under SURVIVAL EQUIPMENT. But in addition to the signal mirror you carry with you the windshield rear-view mirror of your car will make an excellent passive signal mirror to attract attention in the event of mechanical failure. If those aren’t available a string of CDs can be fashioned into a similar, but less effective passive signal device.

Figure 21 – Swinging dashboard mirror

Those mirrors are usually removable by taking out a couple of screws. Thread a length of string through one of the screw holes and suspend the mirror from a tree limb or improvised tripod on some high place near your vehicle.

Figure 22 – Swinging side mirror

The suspended mirror will respond to a gentle breeze and twist in the sunlight sending flashes of reflected sunlight visible for miles in all directions. If the side mirrors on the vehicle can be removed easily do the same with them.

Figure 23 – Adding mirror fragments

If you have a broken mirror or extras a touch of super glue will attach them to the non-reflective surface of the suspended, twirling rear-view mirror to provide more flashes in the distance to help your rescuers locate you.

Figure 24 – Camera strobe for signaling

Any camera or camera flash will serve as an effective nigh-time signal device.

Figure 25 – Hot shoe strobe

Camera flash or strobe:

From a hilltop at night if you see headlights in the distance or an airplane overhead the flash, or repeated flashes of a strobe will almost certainly attract attention. Think of it from the perspective of that pilot, or the person behind those headlights. They are looking into a bowl of darkness. Suddenly, where nothing should be, they see a series of bright flashes. If they know someone’s lost and a search is in progress they’ll immediately deduce the meaning of the flashes. If they’re unaware anyone’s lost, or if a search isn’t in progress, they’ll remember the flashes and wonder about the source. They might wonder enough to mention it to an air-traffic controller, police officer, or phone a rancher in the area to ask what’s going on out there at night.

Figure 26 – Spray-can night signal

Hair spay, insect spray, spray paint, spray deodorant, engine starter fluid spray (ether), vaporized petroleum penetrating lubricant and many other canned, compressed sprays can be used to create a flashes of light at night if you don’t have a camera flash.

Point the spray nozzle away from you, holding it one hand with a lighter or lit match in the other, six inches in front of the nozzle and four or five inches lower than the route of the spray. Press the top of the nozzle and release it to send a mist above the flame lasting no more than a second. The mist will explode in a flash 3-4 feet in diameter in front of you.

You’ll want to practice doing this a few times by daylight before trying it in the dark. Be particularly careful to point the spray nozzle away from yourself and hold the flame at least 18 inches beyond, still further away from you.

The resulting explosion and flash will probably singe any exposed hair on your hands and arms, but unless you direct the spray directly onto your shirt or flesh you won’t be burned.

Use this method in the same way I’ve suggested using a camera strobe or flash and only in the event you see distant headlights or the sound of an aircraft overhead gives you cause to think the flash likely to attract attention.

Figure 27 – Laser pointer

Laser Pointer. If you have one, sweep anything that looks promising. If you sweep that ranch house you can see 10 miles away it will get you some attention eventually. These are available for a couple of bucks and they’re tiny.

Military and civilian commercial aircraft evidently have sensors to alert pilots when they’re being flashed by laser pointers these days. I read a news account recently of a number of incidents being investigated by the FBI in several cities concerning aircraft being flashed by laser pointers. The accounts suggested the sources for the light was easily traced.

SECTION 10: SURVIVAL AND EMERGENCY SUPPLIES

Fire starter: A butane lighter, even if you don’t smoke is a must. A film canister filled with cotton-balls soaked in candle wax will finish off your fire starting ensemble.

Water: Under some circumstances, there’s no such thing as enough.

Clothing: A light jacket for cool desert nights, even if you don’t plan to stay the night. A pair of extra socks.

Bedding: Blanket or bag, just for emergencies, can help you enjoy an unintended night under the stars. If you don’t have a sleeping bag or blanket you’re going to want some sort of protection from the ground surface and the cold. Explore your options. A seat cover might provide you with a makeshift ground cloth or blanket. Use your imagination and exploit whatever you have available before you begin walking.

Cutting tool: Never mind the big Buck skinner. A Victorinox Swiss Army knife with a cutting blade, a saw tooth blade, and can opener is a good choice.

Cyumel light sticks: 12 hours. A few in the trunk can serve as night road flares, but they can also give you something to wave around after dark when you are trying to get the attention of an SAR aircraft. If you are lost and carrying one don’t light it to check whether the water has bugs in it. Wait until the second night you are lost to give the air search time to get rolling.

Light: For many years I carried a small candle-lantern while trekking. It served, though the candle-life wasn’t a lot longer than the cell-life of a flashlight battery. Today, that candle lantern has been replaced by an amazing piece of technology.

Figure 28 – Wind-up flashlight

This LED flashlight puts out an amazing amount of light lasting half-hour after a couple of minutes cranking to recharge the battery. I picked it up at a discount house for less than $10. The focused beam will light objects 40 yards away enough to make them recognizable. It’s a tough, durable, practical piece of equipment I wish had been invented half-century earlier. It would have saved me wax-stains on dozens of shirts, trousers, tents, sleeping bags and tarps. This piece of gear seems to me to be the next-best thing to primitive in every way.

Spotlight: Another piece of technology worth having in the trunk of the car in an emergency is a kind of spotlight that’s come available during the past few years. The one I have cost around $10 and puts out a beam of light that might blind an airline pilot flying 30,000 feet overhead. A freaking MILLION candle power.

Figure 29 – Signal spotlight

This one can actually be recharged from the cigarette-lighter socket on the car, or from house-current. It occupies a space of about 6 inches across and a foot high. A truly useless, extraneous piece of equipment under most circumstances. Unless you happen to find yourself broken down a long way from help you’ll probably spend the next decade cursing yourself for ever buying it. But, I do own one and I’m glad for it.

Firearms. I’ve hesitated to approach the subject of firearms. People who own them and have them nearby in an emergency, one supposes, know how to use them. Those who don’t have made a choice not to have them, won’t have one available in time of need, and don’t want to know about them. On the other hand, if there is a firearm and if the person who has it doesn’t know anything about such matters, a few basic observations are appropriate. First, if the piece is a handgun, small caliber with a long distance between the sights it’s minutely possible you might kill a rabbit with it. If the piece is a small bore rifle you stand an even better chance for meat, but the weight will probably make it not worth taking with you if you have to trek. As for large bore pistols and rifles, the best use for them in a desert survival situation is to conserve ammo and fire only when someone might hear. Unless you find yourself in a conversation with an outfitter.

Torch: If there’s gasoline in the vehicle and if the fuel pump is working you might be able to make use of the gasoline by disconnecting or cutting the fuel line before it enters the carburetor or fuel injection. Once the line is free, wad a cloth around the end of it and turn on the ignition for a moment. If the vehicle has an electric fuel pump it will immediately engage and commence pumping fuel into the cloth bundle on the end of the fuel line. If the pump is mechanical you’ll need to crank the engine to cause the pump to engage. Soaking the rag will only take a moment. Afterward it can be wrapped around a stick, ignited, and waved in the air at night to attract attention.

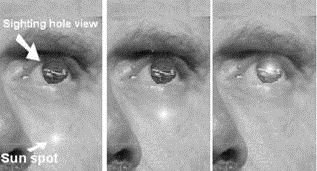

Mirror: If you place a makeup mirror in front of your eye so you are looking over the top of it, reflecting the dot of the sun on the ground in front of you, and extend your arm to full length in front of you, put your finger into the reflected light. Sight along the top of your finger, and move the arm, lighted finger, and reflection from the mirror all together toward the house on the ridge 10 miles away, the airplane above you, the fire tower you can barely see several miles away, and keep at it. It might eventually get you some help.

Figure 30 – Constructing a signal mirror

Some things are so small, easy, cheap and potentially valuable it makes no sense to be without them. A signal mirror is one of those. There’s an easy way to make a foolproof signal mirror out of two small mirrors back to back. Buy two 1-inch square mirrors from the discount store, and a little glue. Draw an X from corner to corner on the backs of each of the mirrors. Scrape off the paint in a 1/4 inch circle at the center of each X, enough so you can see through. Apply some glue to the still-painted area on the mirrors, and stick them together neatly back-to-back.

Hold the mirror up to your eye an inch or so from your face and look at the reflection. You’ll see the spot of light on your face where the sun is coming through the hole in the paint of the two mirrors. Tilt the mirror until the spot moves over the hole in the mirror. Now the mirror will be shining on whatever you are looking at through the hole. The target can be a car on the

Figure 31 – Mirror signaling Step 1

Reflection in the signal mirror and view through the hole

road, an airplane, a house, the eyes of your pet llama, or the circling buzzards. This can be a nice way to amuse yourself while you’re taking a breather from imitating those cartoon characters crawling through the desert.

Figure 32 – Mirror signaling Step 2

This series of photographs illustrates how you focus the reflection on the target. You are looking at the reflection of your face in the mirror. Through the hole in the center you see an airplane. You also see the spot of sunlight that comes through the hole in the mirror. Keep the target in view through the hole and tilt the mirror. You’ll see the spot moving upward toward the hole. When the reflection of the spot of sunlight reaches the hole you’ll see a new glare. The mirror is reflecting precisely on target.

Shelter: A couple of black plastic leaf-bags will serve in a pinch. They pack down small and are tough. The bags can be cut open to make a lean-to, or worn as clothing, one top side, and one bottom side. Something to keep off the dew and night winds can be a blessing. 30 feet of trotline cord will be a plus, if you decide to go for the lean-to. A marble sized rock folded into each corner and tied as shown below will give the cord something to anchor to without tearing the plastic. Leaf bags are surprisingly strong.

Figure 33 – Securing corners on plastic

This type lean-to shelter will hold up under brisk gusts if you’ve been careful securing the corners.

Figure 34 – Improvising to heat water

Vessel to heat liquid: A double fold of heavy tinfoil will do the job if you have nothing else.

Water will heat a lot more rapidly if your vessel is shallow with a large surface area on the bottom. Use your belt for a frame to shape the foil into a shallow pan and reinforce the sides by folding the extra foil back over itself. This will keep the sides from collapsing and spilling your liquid when the foil heats. If you aren’t in a hurry the best method for heating water this way is to place a flat-topped rock close to the flames and let it heat. After the rock is hot, place your foil pan on the surface and let the rock heat the water instead of using open flame. The pan will last longer using that method. Once the water is hot use your handkerchief or shirt tail for a pot holder to pick it up by both sides so you don’t spill the hot liquid. The vessel sides don’t have the strength to support the weigh of the water if you try to lift it by one side.

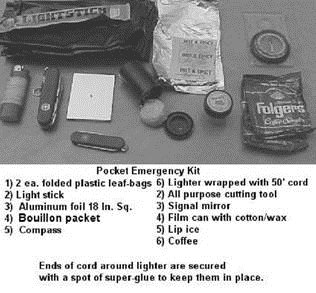

SECTION 10: POCKET SURVIVAL KIT

Figure 35- Pocket survival kit packed