Hi readers. I might have once thought I knew what a massacre was, but time’s eroded my perspective. During the mid-1990s I made the toughest backpacking trip of my life to spend 8-9 days in there to try for a better understanding of the subject.

Here’s the basic story of the events leading to it being named, “Massacre Canyon”:

http://www.livestockweekly.com/papers/97/07/03/3bowser.html

RETIRED GENERAL Michael Cody served in a somewhat more modern army than the men he and others honored recently at Massacre Canyon in New Mexico, but Cody’s army still traces its history to the men who helped open the West. A student of the era and the area, Cody has an affinity for and an understanding of the men who fought on both sides of the conflict more than a century ago.

Massacre In Las Animas Canyon

Led To End Of Apache Victorio

By David Bowser

HILLSBORO, N.M. — Indian legend maintains that rain at a funeral means the gods are weeping over the death of a great man.

Black clouds boil up over the Black Range Mountains as Michael Cody, a retired U.S. Army general, addresses a gathering along Animas Creek. Soldiers and spectators traveled to this clearing to dedicate a headstone honoring those who fought in Massacre Canyon more than a century ago. Three Congressional Medals of Honor were awarded in that clash Sept. 18, 1879, between the buffalo soldiers of the Ninth U.S. Cavalry and the Apache warriors of Victorio.

“The Battle of Las Animas Canyon did not begin on the 18th of September, 1879,” says Cody, who is working on several books concerning the era. “It had its beginning long before then.”

Until 1872, the Tchine, the Red Paint People of the Apache, made their home around Ojo Caliente in New Mexico.

Prior to 1872, there was a reservation at Ojo Caliente for the Tchine. By 1872, miners and ranchers had come, and the Apache were moved.

They were shifted from reservation to reservation until 1876, when Victorio and the rest of the Tchine left the reservation and went to Ojo Caliente. That winter, they surrendered and were taken to the Mescalero reservation near present-day Ruidoso. They stayed until August, 1878.

“Unable to stand it any longer, Victorio and his segundo, Nana, a 73 year-old man, took the entire Tchine nation, almost 600 people, and left the Mescalero reservation to go home to Ojo Caliente,” Cody says.

The Ninth United States Cavalry, the most decorated unit in the history of the United States Army, was responsible for the area. They were headquartered at Fort Bayard under Col. Edward Hatch.

“When Victorio left the reservation, he headed for Ojo Caliente,” Cody says. “When he got there, he found E Company of the Ninth United States Cavalry. It took Victorio about 10 minutes to turn E Company from cavalry to infantry. He killed about 11 people, eight troopers and three civilians, took 68 horses and mules, and headed out.”

Victorio moved south toward Silver City, New Mexico.

“He hit a couple of small ranchitos to get food, to get some ammunition,” Cody says. “Somewhere between Silver City and Kingston, he ran into a militia group made up of miners.”

Victorio’s band killed about 10 men, took another 50 horses and went down the Animas. Victorio had not lost a man.

Two of the 15 graves in this clearing are those of Navajo scouts who rode with the Ninth Cavalry.

“They were from the Sixth Cavalry, but detached to the Ninth,” Cody explains. “They picked up Victorio’s trail and the entire Ninth United States Cavalry went to the field.”

Second Lt. Robert Temple Emmet was on court martial duty in Santa Fe, N.M., when word came of the attack at Ojo Caliente. Emmet traveled 48 hours by stagecoach to Fort Bayard to rejoin his troops following Victorio down the Animas.

“There are several versions of what happened next,” Cody says. “The stories according to the Apache and in army records does not differ much.”

The First Battalion, commanded by Capt. Byron Dawson with Lt. Mathias Day and a Lt. H. Wright, came upon either an Indian woman down by the creek or a couple of Apache warriors who fired shots at the approaching soldiers.

Ignoring the Navajo scouts’ warnings not to follow, the cavalry chased the Indian woman — or the two warriors — across this clearing about a quarter mile and into what has become known as Massacre Canyon.

The canyon entrance is about 30 yards wide with spires of rock on either side. The trail makes an S-curve through the canyon with a rock outcropping that is about 16 yards wide and three yards deep.

“It’s flat as an arrow,” Cody says. “It’s a perfect place to put about 20 guys with rifles.”

The First Battalion, 25 men from Companies A and B of the Ninth Cavalry and perhaps 50 from Company E, remounted and came through the entrance in single file. With the 75 men well inside the canyon, Victorio opened fire.

Sixty-one Tchine lay along the ridgeline. There were 60 warriors and one woman, Nahdoste, the sister of Geronimo and Nana’s wife.

In the first volley of fire, 32 horses fell. The First Battalion was trapped.

The Second Battalion under the command of Capt. Charles Beyer with First Lt. William H. Hugo and Second Lt. Emmet heard the gunfire and came down the Animas.

As they approached Massacre Canyon, Victorio lifted his fire, let them get close, then opened up again. Victorio now had four companies of cavalry pinned down.

“All this started at 9 a.m. on 18 September 1879,” Cody says. “Victorio followed a classic method of warfare: kill the horses first, then kill the troopers at your leisure — a perfectly executed ambush.”

Late in the afternoon, Lt. Day with a small detachment attempted to break to the head of the canyon to climb up the steep slope and come back along the ridgeline to roll Victorio’s flank.

“As he got on the ridgeline,” Cody says, “the Apache held their fire until he was totally exposed, then opened fire on his flank. Day and his detachment were pinned down.”

Hugo and Emmet with a detachment outside the canyon attempted the same maneuver on Victorio’s other flank. They tried to come up a little canyon on the other side of the ridgeline, climb the massive slope and roll the Apache flank.

“The Apache let him in, then opened fire on his flank,” Cody says.

Now Hugo and Emmet were pinned down.

“By late in the afternoon, it was time to get out of there,” Cody says. “Troops on the valley floor were down to two or three rounds of ammunition per man. The order was given to withdraw. Lt. Day at the head of the canyon refused to obey. He had a man, one of his troopers, wounded on the ridgeline above him, and rather than obey the order, he climbed onto that ridgeline under fire to rescue his trooper. For this the commander of troops threatened him with court martial for refusal to obey his order to withdraw.”

Hugo and Emmet were also given the order to withdraw. They fired three volleys in an attempt to get the Apaches’ attention so the people on the valley floor could get out. It worked, but Emmet also refused to obey the order to withdraw.

“Five of his troopers, buffalo soldiers, were exposed on the ridgeline above him,” Cody says. “Rather than obey the order to withdraw, he climbed the ridgeline to get above those five, drawing fire, then laying down a base of fire so his men could escape. For this Lt. Robert Emmet was threatened with a court martial for refusal to obey an order.”

On the valley floor, Pvt. Freeland was wounded in the first volley. By late afternoon, he was in bad shape. He had taken a bullet through his thigh, breaking the bone.

First Sgt. John Denny, lying on the ridgeline about a quarter mile away, ran through the exposed rock-strewn area to pick up Pvt. Freeland, got him on his shoulders and ran back 400 yards, all under direct fire.

Day, Emmet and Denny were each awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for their actions.

The field commander, Lt. Col. Nathan A.M. Dudley, who threatened both lieutenants with court martial for not withdrawing, was relieved by Major Albert P. Morrow.

Morrow and the Ninth Cavalry, working with the Tenth Cavalry, continued to chase Victorio.

“The 10th Cavalry blocked the water holes,” Cody says. “The Ninth followed the Apache. The Ninth kept the pressure on the Apache until October 1880 at Tres Cabrillos, when Col. Juaquin Terrazas of the Mexican cavalry got into the act.”

The Mexican government granted permission for the U.S. Army to follow Victorio into Mexico. Morrow’s scouts pinned Victorio down at Tres Cabrillos. Victorio had women, elders and children, and many wounded. They were out of food and ammunition. Morrow informed Col. Terrazas of his intention to surround Victorio and ask for his surrender.

At that, Terrazas withdrew the Mexican government’s permission for the U.S. Army to operate south of the border, insisting that Morrow return to the United States. The Ninth Cavalry wheeled and went back to U.S. soil.

Terrazas surrounded Victorio’s band and slaughtered them.

“It was an abject massacre,” Cody says. “He slaughtered them. He took about 100 women and younger children — not the real little ones — those they eviserated and smashed their skulls. The ones that were old enough, they kept for slaves.”

But Nana, now 75 years old, was out with Nahdoste and 14 warriors gathering provisions. Author Max Evans, whose book on Nana is to be published next year, claims that an Apache medicine woman, Lozen, was also with Nana. According to Evans, Lozen could sense approaching danger. If she had been with Victorio, Evans reasons, the band would have escaped.

“When they got back, they found this slaughter,” Cody says. “That was the beginning of the Nana vengence campaign.”

Every raid that Nana led from then on, he took no prisoners. Nana and his warriors burned and destroyed. Finally, they caught Col. Terrazas.

Nana and his band finally came in.

“When Nana did surrender, he was 76 years old,” Cody says. “They took him to the reservation in Oklahoma and he died there, but he died as an unrepentent hater of the Mexican people. It’s understandable. Honorable men fight for dishonorable causes, but that doesn’t take away from the fact that they are honorable. Nana was an extraordinary, historic figure.”

The services here were the result of seven years of work by Gene Ballinger, a historian and author; Cody and a number of others representing such groups as the Medal of Honor Society, The Buffalo Soldiers Society and other parties interested in preserving New Mexico history.

Twice during the services here on the F Cross Ranch of Jimmy Bason, rain splattered the soldiers and civilians gathered along the Animas.

That evening as most of the participants and spectators sat in their motel rooms in Truth or Consequences or at the S Bar X bar in Hillsboro, the clouds opened up in this rugged, arid land, washing the long-ago battlefield with a heavy mourning rain.

As you can see, it’s not easy to escape a lot of theatrical hand wringing and rhetorical horse manure carried along as baggage when it comes from some retired Army scud with the name Cody worn as a pair of crutches. A dozen-or-two decades establishes fairly well what those soldiers died for in that canyon.

Even though there’s a USFS road [maintained by US taxpayer funding] leading in from the East, access to the site is denied by the owners of the giant ranch. For you, me, and any Mescalero Apaches who’d like to see where their ancestors taught the US Army a few basics about ambush.

The only way in involves backpacking down from the Mimbres Divide. Tough tough tough tough.

But worth every minute of it. Every drop of sweat it takes to get there.

A person can still examine the pockmarks on the watermelon-sized rocks those soldiers were trying to squinch themselves down behind. Can still pan spent, deformed rounds out of the canyon bottom. See the inside of the mind of Victorio, where he placed his men, the landmark selected to commence firing when the troops passed it.

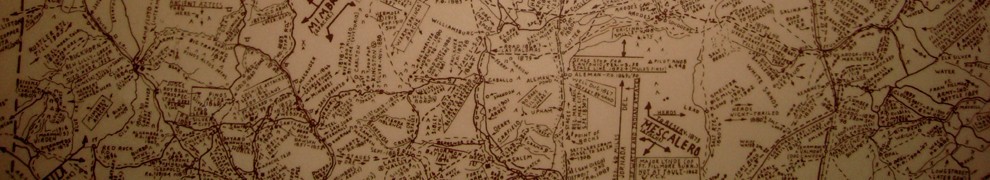

In those days guys like Cody and Gene Ballinger were already doing a lot of posturing and flag waving about the 12 unmarked graves on the plateau you can see in the picture toward the center. Cody, Ballinger et al didn’t have to pack in. The rancher to the East allowed them access by the Forest Road.

So during my eight days in there part of the way I passed the time was digging down a couple of feet below the surface various places in the canyon, plateau, and further up Animas Canyon, carefully gathering and placing rocks. Creating enough other unmarked graves to make it difficult for them to go in and rob artifacts out of the actual graves. Which I believed then and now, they were in the process of doing.

Old Jules