When Louis Nizer penned The Implosion Conspiracy it might be said enough time had passed to provide perspective. Two decades had passed since the trial and execution of the Rosenbergs rocked the nation. Nizer disliked Communists, asserted he’d refuse to defend one in his profession as a defense attorney. However, he wrote a lengthy analysis of the trial, the transcripts, testimonies, the individuals involved in an even-handed manner that wouldn’t have been possible during the Commie craze days of the events.

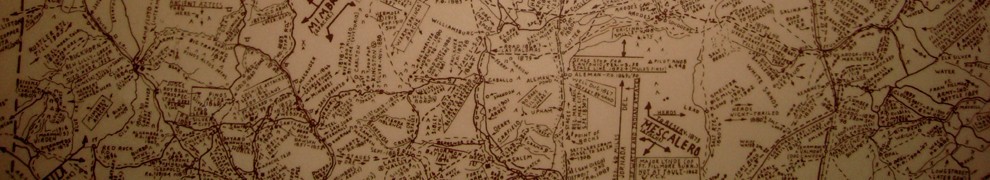

Basic events leading to the trial: The US was developing the atomic bomb at Los Alamos, New Mexico during the late stages of WWII. The information was being shared with the US Ally, Britain, but kept secret from the US Ally, the USSR. Elaborate security measures were in place to assure the developments remained the exclusive property of the US and British governments. Elaborate almost beyond description, devised by the US military and the FBI.

But the British liaison to the project was physicist Klaus Fuchs, a spy for the Soviet Union. The Germans knew Fuchs to be a Soviet spy, but the British and Americans didn’t, until they gained access to records captured as they advanced into Germany.

Aside from Fuchs, the other USSR source for information about developments at Los Alamos was David Greenglass, a US Army machinist and brother to Ethyl Rosenberg. Greenglass had been a Communist his entire adult life and had been separated from an earlier military job because of questions about his loyalty and honesty.

David Greenglass stole the crucial secrets of the lens molds used to detonate the bomb, the implosion device. By hindsight, it’s clear he did it for money, for the same reasons he stole automobile parts, uranium, anything he could lay hands on to sell on the black market.

Greenglass passed the secrets to his wife, Ruth, who passed them to Harry Gold. Gold was the direct connection to the Soviet spymaster, Yakovlev, in the Soviet Embassy. It’s clear enough from everything provided in evidence and testimony that Gold was a man without loyalty to any nation, ideal, idea, or human being other than himself. He did it for the money and for no other reason.

The testimony of Greenglass, awaiting trial for treason, and his wife, Ruth, who was never charged, provided the testimony connecting Julius and Ethyl Rosenberg to the plot. The witness stand accusations by Greenglass against his sister and brother-in-law, and the corroborating testimony from his wife, who didn’t yet know whether she’d be charged, constituted almost the only evidence of the prosecution. The other witnesses directly involved in the plot mostly did not know the Rosenbergs, or barely knew them and knew little of their activities.

Because of the weakness of the government case insofar as testimony and physical evidence of the Rosenberg involvement in actual spy activities, the focus of the prosecution became a trial of Communist ideology. Witnesses who knew nothing about the plot, the bomb secrets, the Rosenbergs were called to testify about how they’d switched their own loyalties from Fascism to Communism, then become loyal US citizen-experts making a living selling books and giving lectures on the insidiousness of Communism.

The trial transcripts excerpts Nizer provides make it clear the Defense had two opponents: the US Attorney prosecutor, and the judge, who constantly intervened, interrupted, interjected in ways clearly intended to prejudice the jury against the defendants.

The key players who gave, or sold the atomic bomb to the USSR in 1945 went free, or were given relatively light sentences.

The Rosenbergs, clearly Communist idealists, possibly part of the plot, died in the electric chair.

When Allied forces found documents in Germany revealing Fuchs as a Soviet spy the chain of resulting indictments followed a path to almost all the conspirators except the Rosenbergs. Before spymaster Yakovlev fled the US, during his last meeting with Gold, he made the following observations:

Yakovlev: Don’t you remember anything I tell you? You’ve been a sitting duck all this time. We probably are being watched right now. How we pick such morons I’ll never understand! We’ve been living in a goldfish bowl because of you. Idiot! Idiot!

I am leaving the country immediately. I’ll never see you again. Just go away. Don’t follow me.

He went.

But the answer to Yakoviev’s question is worth an answer. They recruited from the US Government, the US military, from US universities, from US businessmen.

From the same pool of applicants who later sold their industries, their industrial tools, secrets, capabilities, economies, and debts to the Peoples Republic of China and other foreign nations.

They weren’t Communists, like the Rosenbergs. They were opportunists, entrepreneurs, devil-take-the-hindmost politicians, like their descendants a few generations later.

Old Jules

Today on Ask Old Jules: Value of Animal vs. Human Lives?

Old Jules, does an animal’s life mean as much or nearly as much to you as a human’s, or do you feel animals are insignificant/worthless in comparison? Also, do you believe it is ever morally right to harm/kill animals? What about humans?